There was a time not too long ago when the question “Do buildings impact health?” was up for debate. The conversation has finally shifted away from skeptics and towards leaders who are finding ways to design, build and manage facilities that prevent harm and heal people and the environment. But as the Healthy Building Movement grows, another question has emerged: how do we ensure healthy buildings work for everyone, not just a select few?

There was a time not too long ago when the question “Do buildings impact health?” was up for debate. The conversation has finally shifted away from skeptics and towards leaders who are finding ways to design, build and manage facilities that prevent harm and heal people and the environment. But as the Healthy Building Movement grows, another question has emerged: how do we ensure healthy buildings work for everyone, not just a select few?

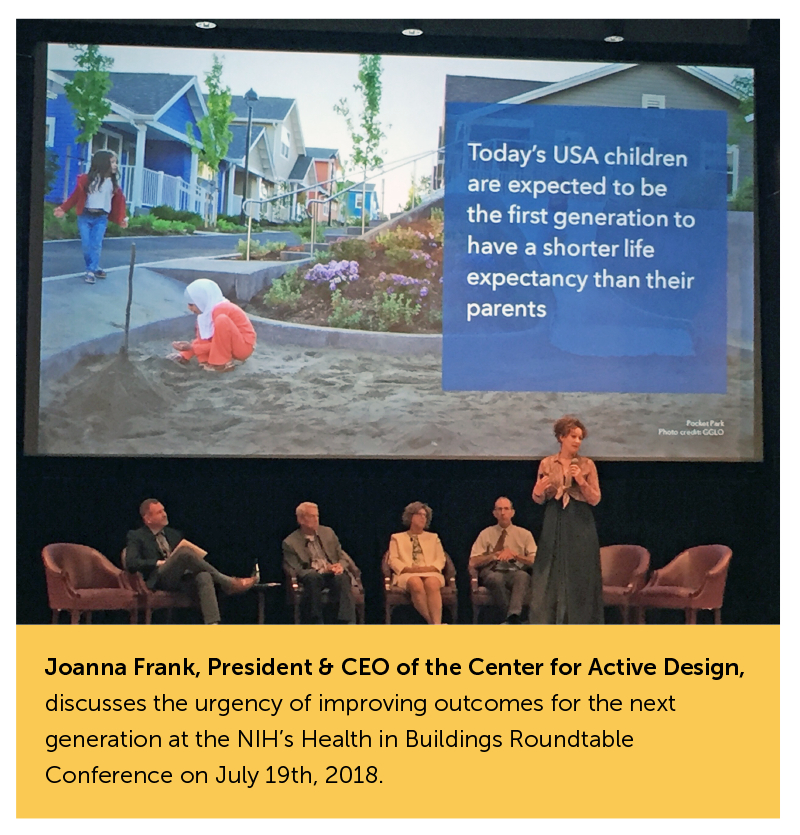

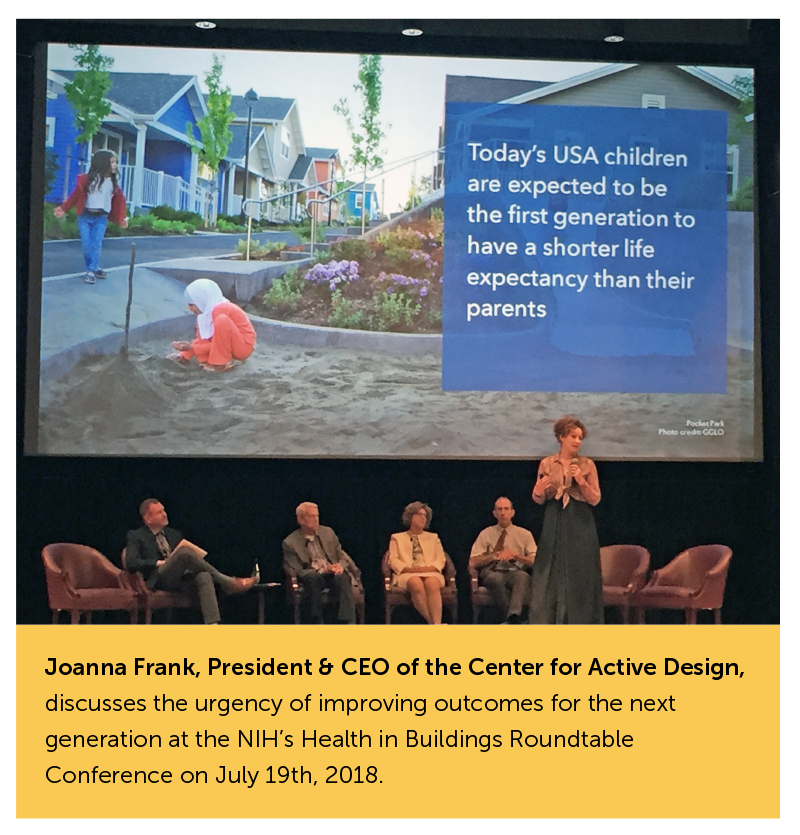

This was one of many questions posed during the third Health in Buildings Roundtable (HiBR) Conference hosted by the National Institutes of Health last week. At the conference, over 100 attendees from the “building business” learned about healthy building best practices and research insights from leaders in academia, the public sector and private entities. While “Making Connections” across sectors and disciplines was the official theme, achieving equity emerged as a prominent motif.

Many health systems have already taken steps to be a part of the Healthy Building Movement by choosing to design and construct environmentally-sustainable spaces which prevent harm, promote healing for patients and support staff wellbeing. Some have also begun to work towards equity by addressing social determinants of health and reducing healthcare disparities. But there are only a few who have started to do both at the same time.

As the healthcare industry advances in its adoption of healthy buildings, we must seize the opportunity to engage in equitable processes or risk repeating the exclusionary mistakes of the past. Inspired by the presentations during Day One of the conference, I’ve outlined six ways that healthcare systems could work together with planners, architects and designers to equitably construct healthy healthcare facilities and promote community health.

- Engage community members in the design process. Engaging stakeholders in the design process – from owners to providers to patients – is already an industry standard. But our focus on the “end user” leaves a gap: the surrounding community. The people who will live and work around a facility may not be your target market today, but by inviting their perspective you can cultivate a positive reputation that could turn into future business. Local organizations are experts in their own neighborhoods and can provide valuable context that is necessary to inform a successful design for that community. Click here to see how Array empowered a Youth Advisory Council to inform the design of a new outpatient clinic at Nemours duPont Pediatrics in Deptford, NJ.

- Integrate local experiential knowledge into spatial analyses. Knowing the elements of the built and natural environment is not enough to understand how it is perceived and used, especially by vulnerable populations, and what opportunities there are for improvement. For example, a database of community resources may not accurately differentiate between a grocery store and a convenience or liquor store. Streetwyze is one app that is hoping to change that. By using online and on-the-ground engagement of residents, it collects data on community assets to serve as both a “neighborhood navigator” and database for designers, planners and architects, bridging the gap between traditional sources of spatial data (e.g., Walk Score) and the lived experience of community members.

- Create spaces that build trust and give agency. Spaces have the potential to foster or impede civic wellbeing, not just physical health. The Center for Active Design recently published Assembly: Civic Design Guidelines, which provides evidence-based design and maintenance strategies for creating public spaces which strengthen trust, appreciation, participation and stewardship. If we view all healthcare facilities as public gathering places for patients and caregivers, we can apply these strategies and align them with patient engagement and experience initiatives.

- Use wayfinding to improve language access. We already understand the importance of investing in wayfinding to improve the patient and caregiver experience at hospitals and clinics. However, as university-educated designers, we often forget that signage depending solely on words will not meet the needs of people with low literacy, cognitive disabilities or limited English proficiency. Strategic use of symbols, universal phrasing and translation, vetted by local stakeholders, can empower a broader group of patients to navigate and access resources.

- Educate your maintenance staff. Building staff are key players to making green buildings work and ensuring they keep working in the long-term. Simply handing staff a large manual or providing a one-off intensive training will not yield the desired results and could lead to costly repairs and re-work. Within the design of initial and ongoing training for maintenance crews, there are opportunities to make education more effective and approachable for individuals with low literacy and unreliable internet access. We can also go further and use these trainings as a channel to offer staff a way to gain lifelong, marketable skills.

- Build relationships with affordable housing developers. One reason why the Healthy Building Movement has not reached vulnerable populations is the lack of incentives for affordable housing developers to build green and healthy buildings. Some health systems, such as Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, are directly investing in development and housing to promote community health. Not all health systems will be able to offer financial incentives, but they may be able to share their expertise and connections as part of their community benefit strategy to help developers find incentives or identify best practices for building healthier spaces.

At Array, we recognize that by working with our partners to proactively build equity into our projects has long-term benefits for the system, staff, and their patients. Let’s explore how we can help identify your community’s needs and design equitable processes and facilities.

Blog authored by Catherine Castillo, former strategic planner with Array Advisors.